Recreating the Medallion of the Last Vestal Virgin of Rome

It comes as news to a lot of people that those beautiful white statues you see of Roman gods, heroes, senators and Caesars weren’t always pure white. In antiquity, they—along with most monuments—were painted in vibrant colors. Even after centuries, we can still see traces of color on many statues.

But it didn’t stop with paint. Statues were often adorned with clothing and jewelry, too. In fact, the statue of a god or Caesar was probably better dressed than your average Roman.

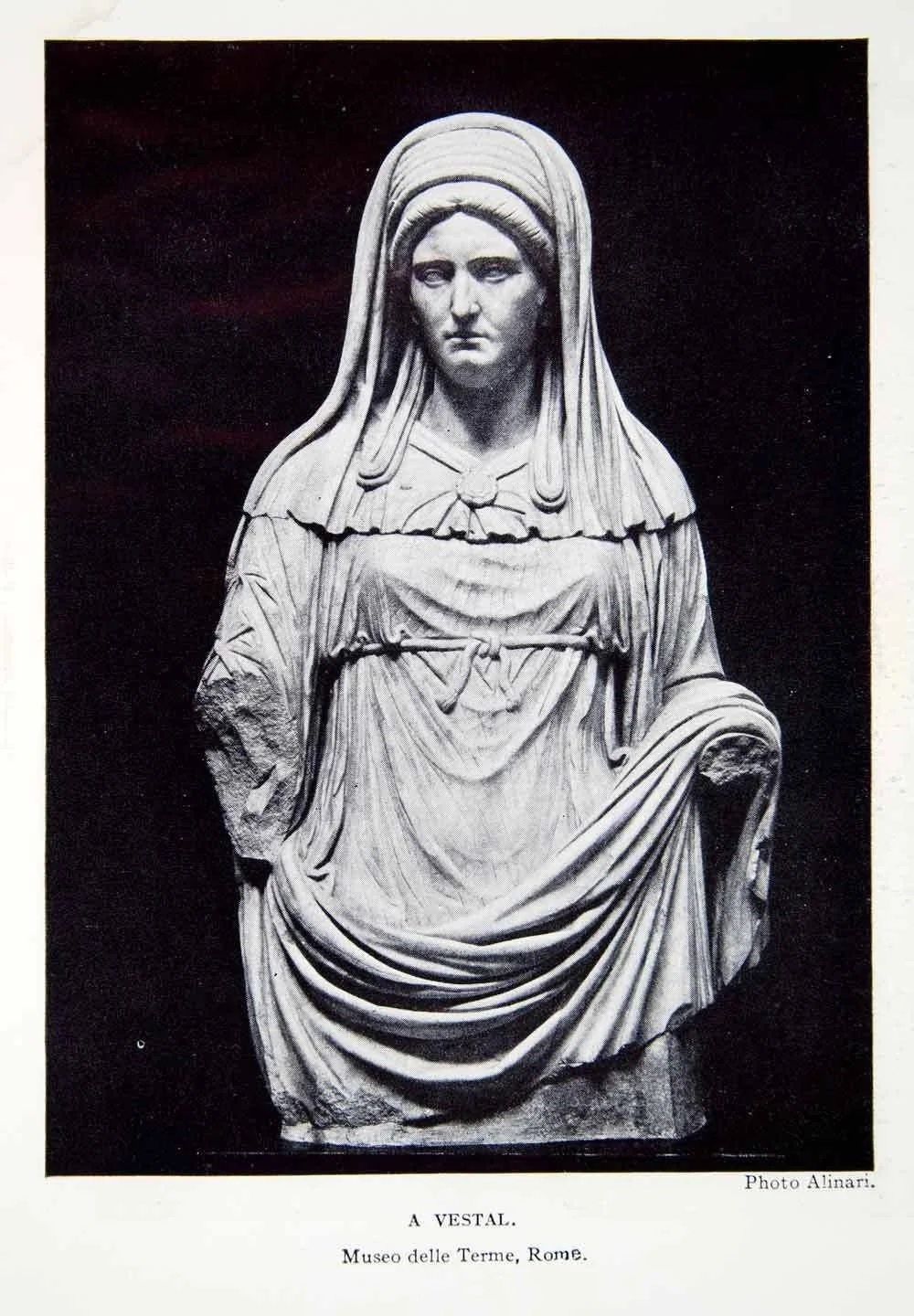

Because the Vestal Virgins—those priestesses who tended the goddess’s sacred flame in her temple—were so respected and important, they too had statues made in their honor. You can see some of them in the ruins of the House of the Vestals in the Roman Forum, as well as in museums. These were statues that, at the very least, would have been embellished with fine paint and jewelry.

Let’s take this statue of a priestess, for example. It displays traditional Vestal attire, including the infula—or headband—under the veil. This would certainly have been painted red and white. If you look where the arrows are pointing, you can see a number of holes in the upper body. This is where a necklace, most likely a very expensive necklace, was affixed to the statue.

And as you can also see, if we add just a hint of color and ornamentation, we can catch just the faintest glimpse of what the ancient Romans saw when they looked at a statue of a Vestal Virgin.

But this video is about a specific Vestal –Coelia Concordia, the last chief or great priestess of the Vestal Order, a position called the Vestalis maxima. She was the last to serve in this capacity before the sacred fire of Vesta was extinguished in the temple on the orders of the Christian emperor Theodosius.

When I was researching her for my novel, called Coelia Concordia, one of the first things I stumbled upon was this classic illustration, found inside a 17th century Latin treatise about the Vestal Virgins. The illustration is of the actual statue of Coelia Concordia that was unearthed in the late 16th century in Rome. Like the illustration, the statue was missing its head and arms.

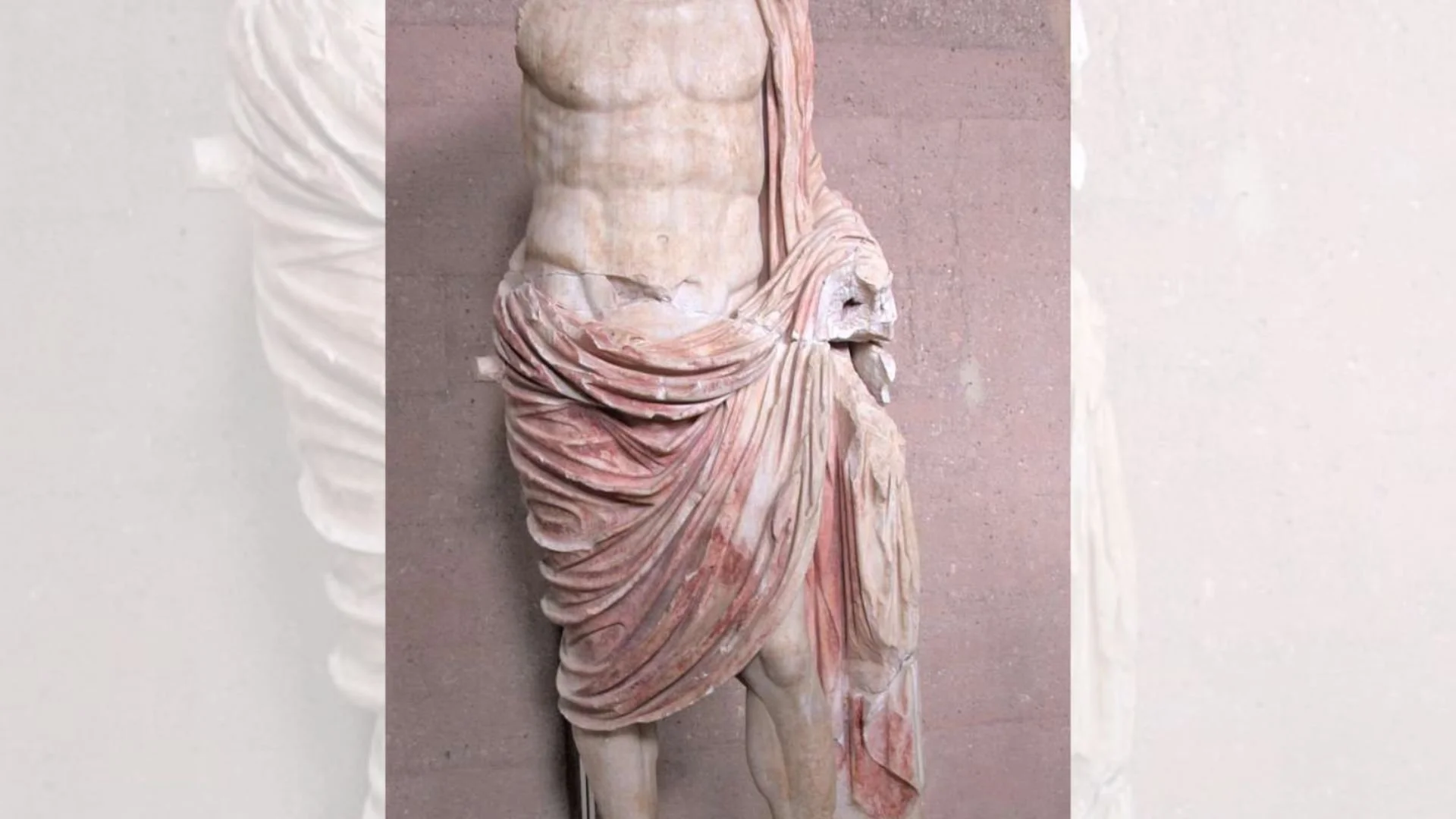

I then tracked down the statue itself, and discovered it had come under the ownership of the Colonna family in Rome not too long after being found. It’s currently in the Colonna Gallery in Rome. That gallery was kind enough to provide me with some lovely professional photographs, which I’ll share with you here.

Photo reproduced with the gracious permission of the Colonna Gallery in Rome.

Photo reproduced with the gracious permission of the Colonna Gallery in Rome.

As you can see, it’s a beautiful marble statue, though it has been reworked to resemble a Muse—a head, arms, and some implements have been added.

However, the same large medallion depicted on the illustration is still there… at least part of it is. This statue originally stood in the latter half of the 4th century, and at that time the medallion would have boasted precious gems. Yet like just about everything else of value, they would have been pried out in later antiquity or when the statue was found. Either way, they are long gone now.

Yet seeing the bare medallion on the statue made me a little melancholy. I kept comparing it to the bejeweled medallion in the illustration. That’s when I had the idea to reproduce it and to see it in color. To see it the way that Coelia Concordia saw it.

After reaching out to a number of jewelers who just weren’t a great fit, I found an award-winning jeweler at Tessa M Designs, and we started experimenting with the dimensions of the piece and types of beading or stones that may have been used.

But to me, it seemed likely that the gemstones would have been red and white, to match Coelia’s infula, and the red edging on her white ceremonial veil... so perhaps pearls contrasted with garnets or carnelian stones. Red to symbolize the sacred fire, and white to represent the purity of the Vestal priestesses.

So we settled on red and white gemstones, set into a large gold disc. And then the jeweler created the piece from scratch, cutting out the metal, making the fittings and really bringing the piece to life.

I like to think that, as the last Vestalis Maxima of the Vestal Order, Coelia Concordia was making a statement with this medallion. She was declaring that what she represented was important. This is hardly the ornamentation of a woman who is willing to fade quietly into obscurity. Yes, her world was changing—there were increasingly restrictive anti-pagan laws coming in at this time, and things were only getting worse for her and for people like her—and yet this bright, bold piece... there’s a certain defiance to it. There’s a certain rage against the dying of the light here. At least to me there is.

I think the finished reproduction is really beautiful. The red and white against the gold is very striking. You can see, obviously, the pagan cross arrangement—so that central red stone might represent the sun – or maybe Vesta’s fire as the sun – with the rectangular stones representing the cardinal directions—east, south, west and north.

The piece looks even more dramatic when placed against white clothing, since the medallion was undoubtedly meant to resemble an actual piece of jewelry worn by the chief priestess in real life. A large piece like this could’ve been worn as a pendant attached to some form of necklace chain or fabric. It could also have been worn as a fibula—a brooch. Large pieces like this were often worn by wealthy and important people in ancient Rome.

And for over a thousand years, the Vestalis Maxima was one of them. Perhaps in some small way, Coelia’s Concordia’s shiny medallion can help us reflect upon just how great these great priestesses really were.