Vestal Virgins: Feminism & Burial Alive

Despite the richness of the Vesta tradition, many people who think Vestal Virgin still think of one thing: the fact that ancient Vestals who broke their 30-year vow of chaste service to the goddess were buried alive. Let’s be honest. Who can blame people for going there? It’s a pretty dramatic image: a young woman being thrown into a shallow grave and trying to claw her way out while dirt is being piled on top of her.

How Did it Happen?

Of course, that isn’t at all how it happened. It was a far more elaborate process than that.

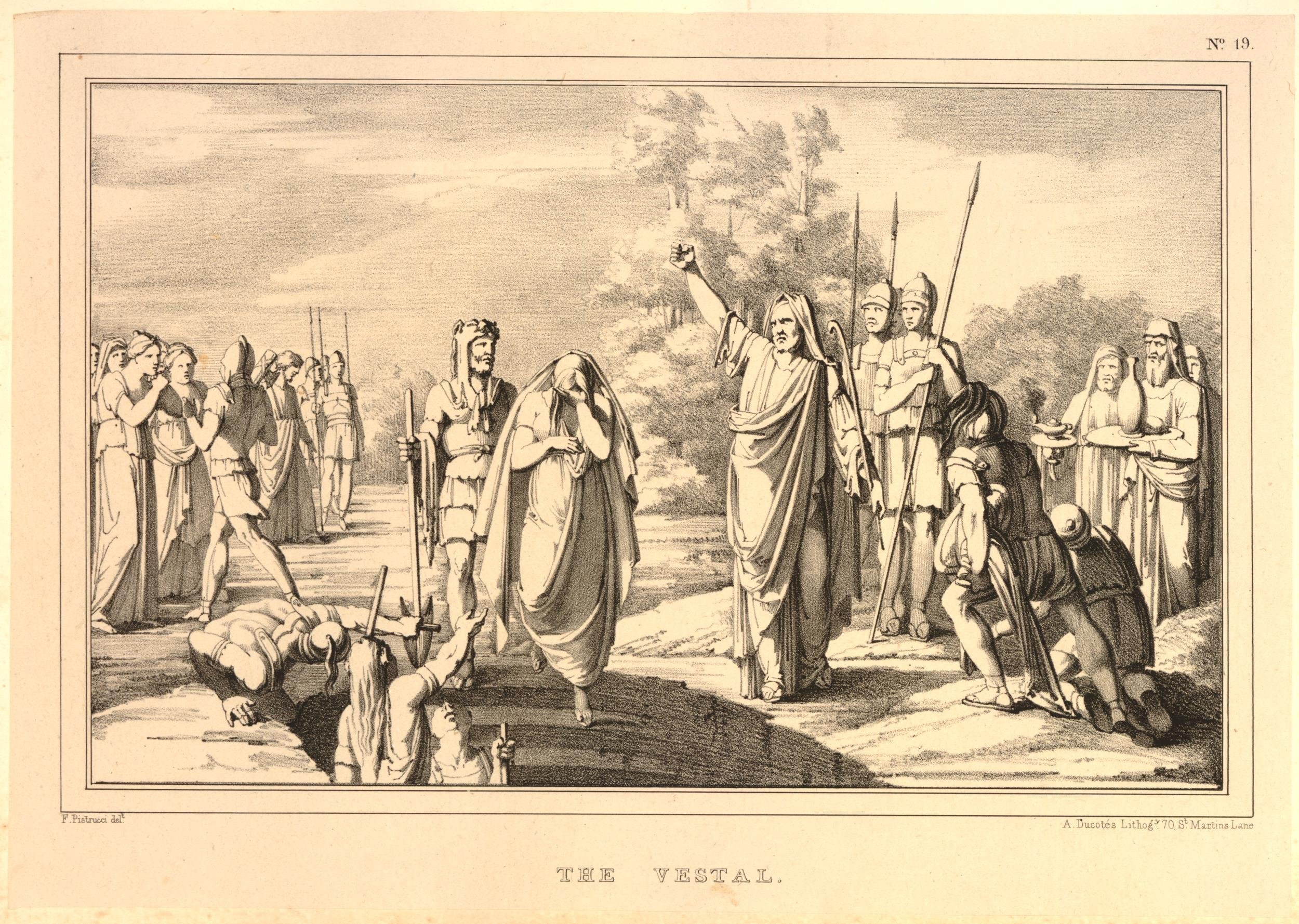

Those who were found guilty of incestum (breaking their vow of chastity) were taken to the Campus Sceleratus or “Evil Field” near the city walls of Rome where they were forced to descend a ladder into a subterranean chamber.

An illustration of a Vestal being forced to descend into a subterranean chamber

They were given enough food, water and light to last a few days. And then the ladder was withdrawn and the lid was closed, sealing off the living world above, and sealing the woman’s fate along with it.

A Vestal in an underground chamber, reaching up to grab a ladder as it is withdrawn

Why Such a Horrible Punishment?

It’s long been believed that this way of punishing a Vestal – bringing about her death without actually swinging a sword – absolved the Roman people of guilt for killing a sacrosanct priestess. Such an approach was a technicality, perhaps, but then again, the ancient Romans were known for that kind of thing.

But I think there’s more to it, for three primary reasons, which, taken as a whole, bring more meaning to this terrible punishment.

First, the historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus writes: “Fire is consecrated to Vesta because that goddess, being the earth and occupying the central place in the universe, kindles the celestial fires from herself.”

Second, Vesta’s divine mother is Ops, a goddess of grain and the earth. It is Ops who blesses the seed below the earth and causes it to sprout to life.

A painting depicting the abundance granted by the fertility goddess

And third, the god Consus - he is the divine consort to Ops, and the god who protects the grain - was honored at a subterranean altar. Like Ops, he cares for the buried seed, and helps bring it to new life from his position underground.

Taken together, it is possible that the punishment - interring a Vestal underground - reflected the ancient belief that, despite her impiety, the Romans were “returning” the priestess to the goddess, and perhaps even giving her a chance at new life. If Vesta is considered the earth, if her own mother and stepfather are chthonic deities (those gods associated with the underworld and the cycle of life, death and rebirth), this makes sense and is consistent with the way the Romans thought.

It may also be possible that interring a Vestal underground incorporated aspects of the Eleusinian Mysteries. These rites were celebrated in Greece but well-known to the Romans. They similarly involved elements of death and rebirth, associated as they were with the goddesses Demeter (the Roman Ceres, a major goddess of grain and the harvest) and her daughter Persephone (the Roman Proserpina).

Wasn’t the Vow of Chastity - and the Punishment for Breaking It - Misogynistic?

It certainly looks that way from the distance of the 21st century. It looks like both the vow of chastity and the punishment for breaking it (which was very rarely carried out, by the way) were simply misogynistic ways to control a woman’s sexuality through fear. It’s hard to argue with that, since that’s precisely what they were intended to do… though not for the reasons we might think.

An illustration of the chief priest whipping a Vestal for breaking her vow of chastity

Here, we must think like the ancient Romans. It does no good to be sanctimonious (we have hardly snuffed out misogyny in our modern world) and it does no good to be lazy, and simply look at history through a 21st century lens. Unfortunately, that lens too often includes a hypersensitivity toward gender issues while simultaneously failing to truly put these things into their historical, social or religious context.

So Let’s Think Like a Roman

Vesta, goddess of the home and hearth, is symbolized by and resides in her sacred fire. In antiquity, her fire burned in Roman homes as well as in the inner sanctum of her temple in the Roman Forum and other cities throughout the empire. The ancient Romans believed that Vesta’s fire protected their world, families and lives, and that if the fire went out, Rome would fall to invading barbarian armies. Their men would be slaughtered, their women and children violated and enslaved, and their entire way of life destroyed.

To prevent this from happening, an order of Vestal priestesses was created to keep the eternal flame alight in Vesta’s temple. The Vestal order was Rome’s only full-time, state-funded priesthood. By guarding the flame, the Vestals ensured the pax deorum – the peace and harmony between the gods and humankind – would remain unbroken.

The Vestal Virgins in the temple, showing the sacred fire to a novice (bottom right)

Choosing suitable priestesses for this duty was essential. After all, the more Vesta approved of them, the more likely it was that she would continue to protect Rome and her people. Because Vesta is a virgin goddess and fire is a purifying element, young girls were selected as priestesses and took a 30-year vow of chaste service to the goddess.

It was believed this state of purity was necessary to perform Vesta’s rites. It also granted priestesses special status to petition Vesta to protect Rome, particularly during times of crisis.

Their virginity was therefore not simply an attempt to control their lives, but rather a consequence of the circumstances required to perform their sacred duties and remain in the virgin goddess’s favor.

Nor did the years of sacrifice that a Vestal made go unnoticed or unrewarded. (Although considering the limited rights and choices most women had at this time, being a Vestal may have been more of a blessing than a sacrifice.) Vestals lived a life of luxury, privilege and relative independence. They were influential in the political sphere and were venerated by society at large. And, after their tenure to the temple was over, they were free to leave the order as wealthy women who were still young enough to marry and perhaps even have children.

But That Punishment…

But back to the punishment of being buried alive. Was it motivated by a culture of misogyny? I sure don’t think so. And again, we must cover that 21st century lens as we look back upon this.

Despite the lower status of women in ancient Rome, despite the law of patria potestas (which gave a father / husband control over the women in his household), the Roman matron was a force to be reckoned with. She had her own ways of advocating for herself, both in the household and even in the courts. Although law and society first and foremost advanced the interests of men in ways that we find pretty awful, ancient Rome by no means “hated” women.

There were great goddesses that men revered as much as women did. There are loving “husband and wife” inscriptions on tombstones. There are many examples of powerful men who consulted their wives in political matters, and made no secret of doing so. There are countless accounts of women successfully challenging the status quo. And right around the 1st century CE, there is evidence that the laws were changing to advance the status of women (more on this in a moment). All of this shows a culture where women were not afraid to push for change. It also shows a level of respect and appreciation for women.

For that reason, I don’t think the Vestals’ punishment was misogynistic. Rather, I think that to the ancient Romans, it was a punishment that fit the crime. If the Vestal’s breach of duty or chastity was a form of treason that put the state at risk, then death was the only punishment.

It’s also worth noting that a Vestal’s male lover usually didn’t fare any better than she did. He would be flogged, bankrupted, and often publicly executed.

A Vestal languishes and awaits death in an underground chamber in the “Evil Field”

The Rise of “Feminism” in Ancient Rome

An assigned 30-year period of chastity – even one that came with some big perks – isn’t something we’d support today. Indeed, there is evidence that the Vestal order itself was challenging this as early as the 1st century CE, particularly under the emperors Vespasian and Titus.

Moreover, the emperors of the early empire (even before Vespasian and Titus) granted “Vestal privileges” to their female family members and other high-status women, thus freeing them from the patria potestas, and giving them the legal right to control their own destinies (and property, and finances…).

In this way, Vestal privileges were an early form of women’s rights that could be expanded beyond the Vestal order. Was this fledgling feminism in ancient Rome? I think so. Of course, the term “feminism” is a poor fit. But the expanding rights of women could not have happened without a belief in equality, or something that was beginning to look a lot like it.

Vestal Virgins enjoy front-row seating in the Colosseum

The Fall of “Feminism” in Ancient Rome

But like any social change, this one was destined to move forward in stops and starts – and its biggest stop was the violence and oppression committed against the Vestal order not by the polytheistic establishment, but by the first Christian emperors. Their androcentric and monotheistic religion demanded the total destruction of a socio-religious order that elevated the status of women.

A fresco called “The Triumph of Christianity” by Laureti, located in the Vatican.

This article is by no means an exhaustive look at the Vestal order. It would take volumes to cover this issue in a comprehensive way, and even then there would be no consensus. My goal here is merely to make us re-think the knee-jerk assumptions we make when we look at Vestal practices and punishments.

I have long believed the Vestal order was an early vehicle for what we today would call feminism. Were it not for the intolerance and agenda of early Christians who found themselves in positions of power, I believe the Vestal order would have expanded its influence and relevance to advance the status of women in the ancient world.

To be sure, this would have happened slowly and imperfectly, but I suspect not as slowly and imperfectly as it did (or has yet to do) in a world dominated by aggressive androcentric monotheism.

After all, the Vestal order and its priestesses had the emperor’s ear. They had influence in the Senate and the religious college, and they moved in important circles. Had they been given more time, perhaps they could have made changes from within, changes that would have spread throughout the empire to improve the lives of women in the larger world.

Had that happened in the ancient world - well, there’s no telling what our modern world would look like by now.