The Last Vestal Virgin and the Fall of Rome: Rome’s Fatal Prophecy

Destruction. Cole. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Ask twenty different people what led to the fall of Rome, and you’ll get twenty different answers. Experts will give you an array of opinions, depending on their area of specialization or what thesis paper they’re writing. There is no single right answer. Political squabbling, weakened borders, a diluted army, disease, economic crises... some even say it was because of lead in the pipes. The fall of the Roman Empire—why it happened, and when exactly—it’s a huge subject.

Yet there were people living in ancient Rome who saw it coming. In fact, an ancient prophecy—a big one—basically predicted the whole thing.

Here, I’d like to talk a little about the fall of Rome—a changing Rome—through the eyes of a very important woman who was about to become very unimportant. The last chief Vestal priestess of the Roman Empire, a woman named Coelia Concordia.

Statue of Coelia Concordia

Photo of Statue of Coelia Concordia, provided by and reproduced with the permission of the Colonna Gallery in Rome. Note: The head, arms and implements were added later, and do not reflect the priestess.

For over a thousand years in Rome, the priestesses of Vesta kept the sacred flame of the goddess Vesta alive in her temple in the Roman Forum. These priestesses were chosen as children from the best families in Rome, took a vow of chastity, and served the goddess for 30 years. During their years of temple service, they lived lives of privilege, esteem and relative independence. Between the ages of 36 and 40, the Vestals were free to retire. And if they did, they took their wealth and connections with them.

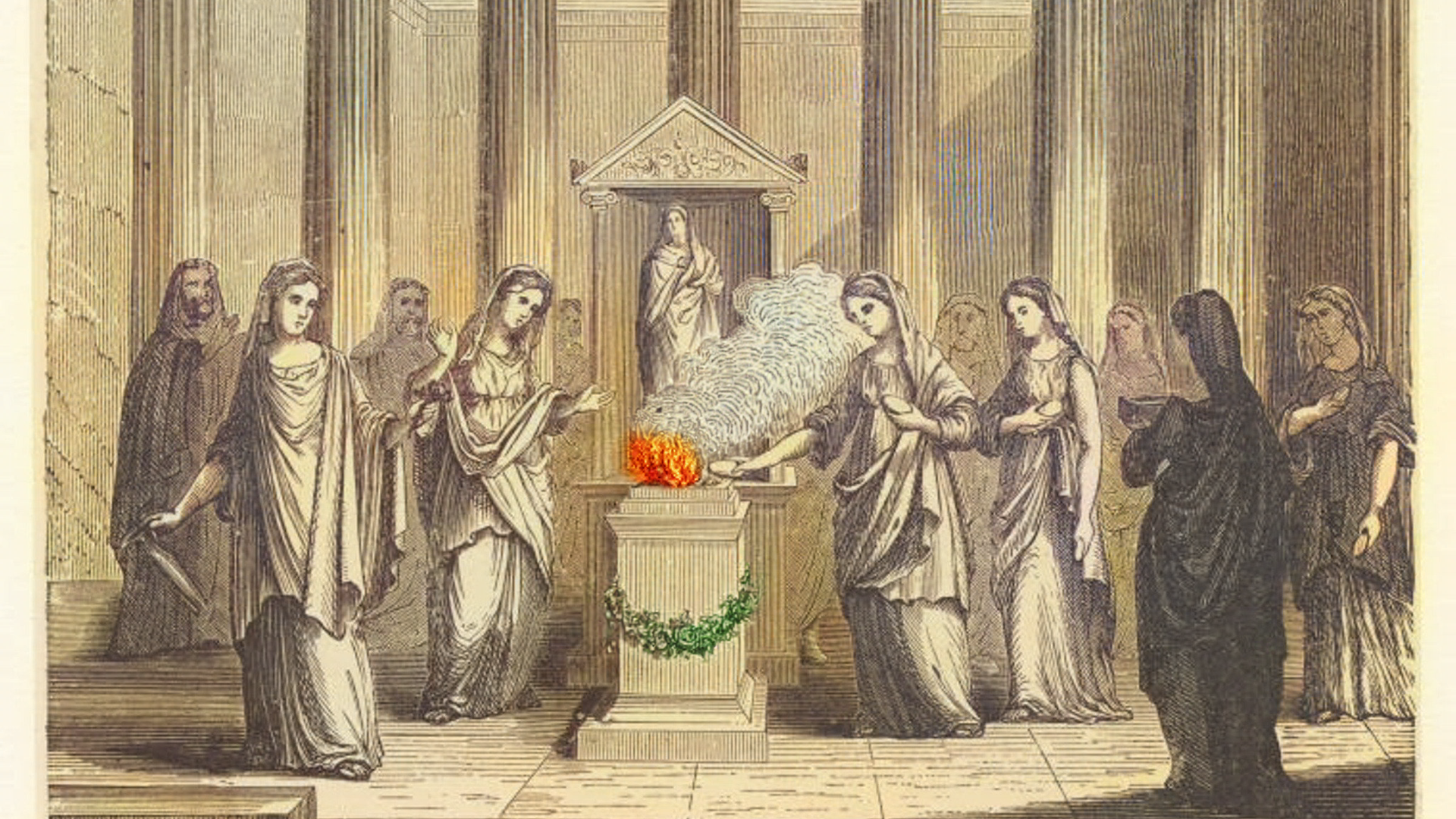

Vestals in the Temple. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

These were the working women of ancient Rome—they worked hard, and they got paid. They were also very respected women, since their priesthood was intimately connected to Rome. In fact, Rome’s legendary founder, Romulus, was the son of a Vestal priestess—Rhea Silvia.

Mars and Rhea Silvia. Rubens. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The Vestals lived in the luxurious House of the Vestals next to the temple in the Forum, but you’d be hard-pressed to say these women led a cloistered life. They performed important public rituals, they ran their own businesses, they supported the endeavors of family and friends, and they attended the best parties. They had special seating in the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus.

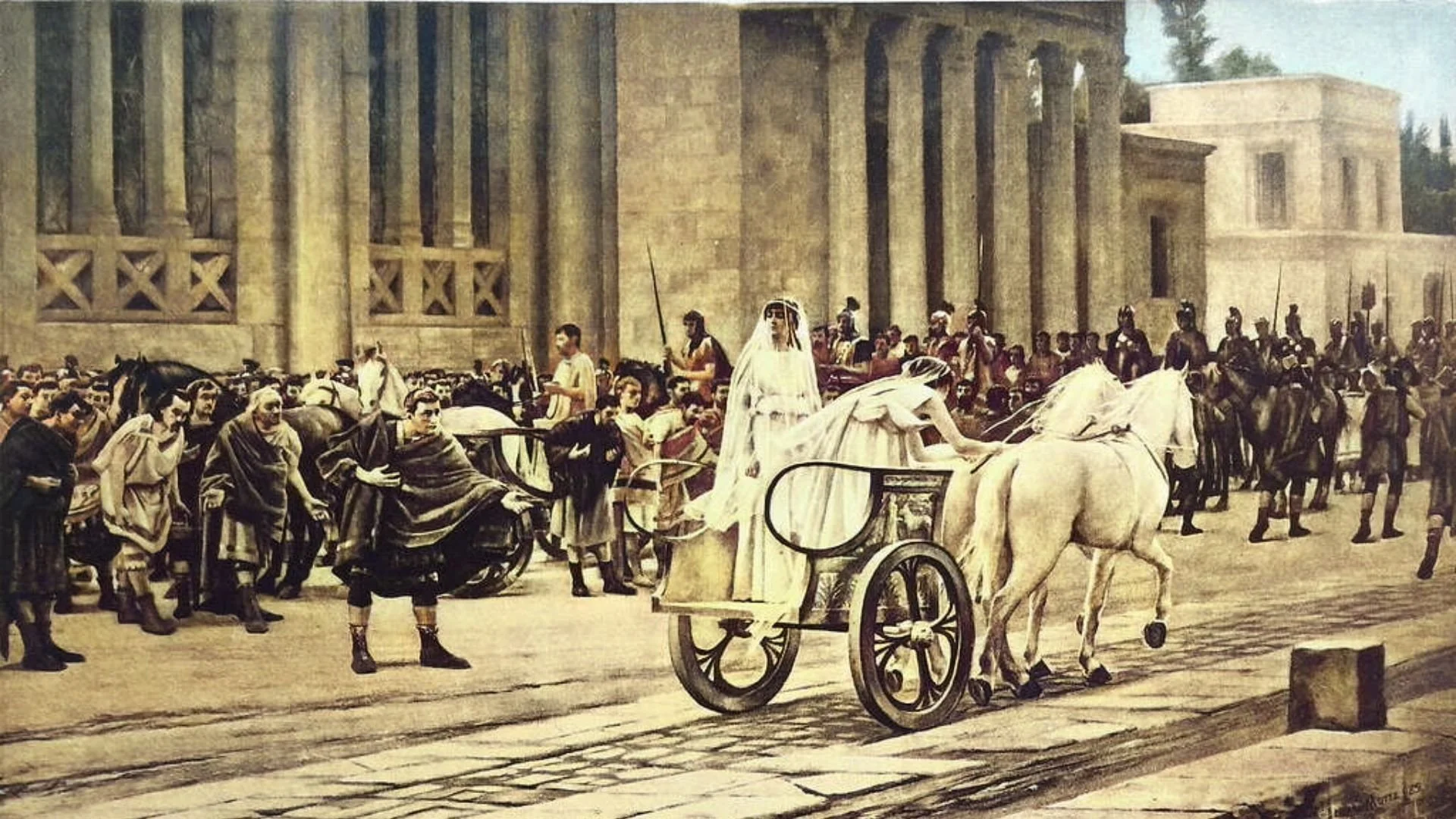

Passing of the Vestals. Motte. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Vestals at the games, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The Ancient Prophecy

The Vestal Virgins had diplomatic functions as well, and were in charge of safeguarding Rome’s vital documents, including the emperor’s last will and testament. Indeed, it was their task to both delivery the will of a deceased emperor to the Senate, and to read it before the senators. They acted as emissaries of peace during times of civil war. The priestesses of Vesta were important. They were so important, in fact, that Rome’s very survival was tied to their duty.

For it was believed that if Vesta’s fire in the temple was extinguished, Rome would lose the protection of the gods, and the city would fall—and that’s the ancient prophecy that predicted it all.

Vestals at the Temple, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Pagan Rome—a Place of Religious Tolerance

Now some people may be surprised to know that Rome was an inherently tolerant place when it came to things like gods. You could pray to just about anyone or anything, and as long as you played nice with the Roman gods and you didn’t cause a fuss, you were good. Ancient Rome was polytheistic – that is, it honored—or if it didn’t honor, at least it accepted—multiple gods.

That status quo was challenged by Christianity, a new monotheistic religion that worshipped only one god. But that wasn’t really what caused conflict—the Romans knew of Judaism, which is similarly monotheistic, but that was an old religion and so the Romans gave it a lot of leeway. The issue with Christianity was that it didn’t play nice with the Roman state religion or customs, and worse, it actively sought to convert people, saying its god was the only god. That undermined Roman social order and the way the state had functioned for centuries.

Augustus at the Temple of Janus, Public domain, Wikimedia Commons. A sacrifice is about to be made to honor the gods and maintain peace.

Yet this wasn’t a huge concern for your average pagan Roman going about his day, at least not until we see those first Christian emperors coming to power... and then things start to get frighteningly intolerant.

The Early Christian Emperors and Powerful Bishops

And perhaps no one felt the strain of this religious intolerance, and the threat of what was happening, more than high profile pagans—people like Coelia Concordia. In the latter half of the 4th century, Coelia, who was born into a plebeian family, rose through the ranks of the Vestal order to become the head of the order, the Vestalis Maxima. Historically, this was one of the very highest positions in Roman state religion and society.

Yet as a pagan priesthood composed of wealthy women who played a prominent role in religion, the Vestal Virgins were certainly at odds with the vision that early church leaders had for their religion.

The bishop Ambrose, for example, defamed the order, likening the Vestal Virgins to prostitutes. In his writings, he claimed the Vestals were immoral and that they were “selling” their virginity to Rome—it’s a twisted interpretation of what the Vestals actually did.

So, even though many Romans still honored those ancestral pagan gods of Rome— you know, Jupiter, Juno, Mars, Venus, Vesta, and others—Christian emperors like Theodosius, influenced by powerful bishops, began to enact increasingly harsh anti-pagan laws.

Statue of Bishop Ambrose, shown with a whip to symbolize the church’s authority over the emperor. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The Resistance

Great is the force of custom, said the illustrious Roman Senator Symmachus as he pleaded with the emperor to preserve the ancient ways of Rome, and to resist the suppression of religious freedom that he saw getting increasingly worse. You don’t have to look far in our modern world to see people like him fighting for their customs, their ancestral way of life, their freedom. People don’t give those up without a fight. It’s human nature, and the ancient Romans were just as human as we are.

Yet just like us, they were subject to the law, including those that targeted the old gods, the temples and priesthoods like the Vestal Virgins. And on one heartbreaking day in the last decade of the 4th century, the Imperial order to extinguish the sacred flame of Vesta in the temple came down.

The Sacred Fire is Extinguished…

Women despair at ancient ruins. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The Effect on Coelia Concordia

We can only imagine how Coelia Concordia—who had served in the temple since childhood, and who was now responsible for the order, must have felt when that happened. We know a little bit about her from a few ancient sources, which I’ve dramatized in my novel Coelia Concordia, and I think it’s safe to say that she was a strong-willed woman. Did she feel angry? She must have. Did she feel despair or was there still some hope that things might change? Did she feel a sense of failure? As the last high priestess of the ancient order, we can certainly sympathize with her sense of loss.

But for a woman like Coelia—like all the women who served as priestesses in ancient Rome—it wasn’t just a matter of seeing their gods banished. It was about seeing their role in society go from respected to ridiculed. From sacred to slandered, even demonized. There would be no more goddesses in Rome, no more priestesses.

Statue of a Vestalis Maxima in the ruins of the House of the Vestals. Note: the colorization and necklace have been added for effect.

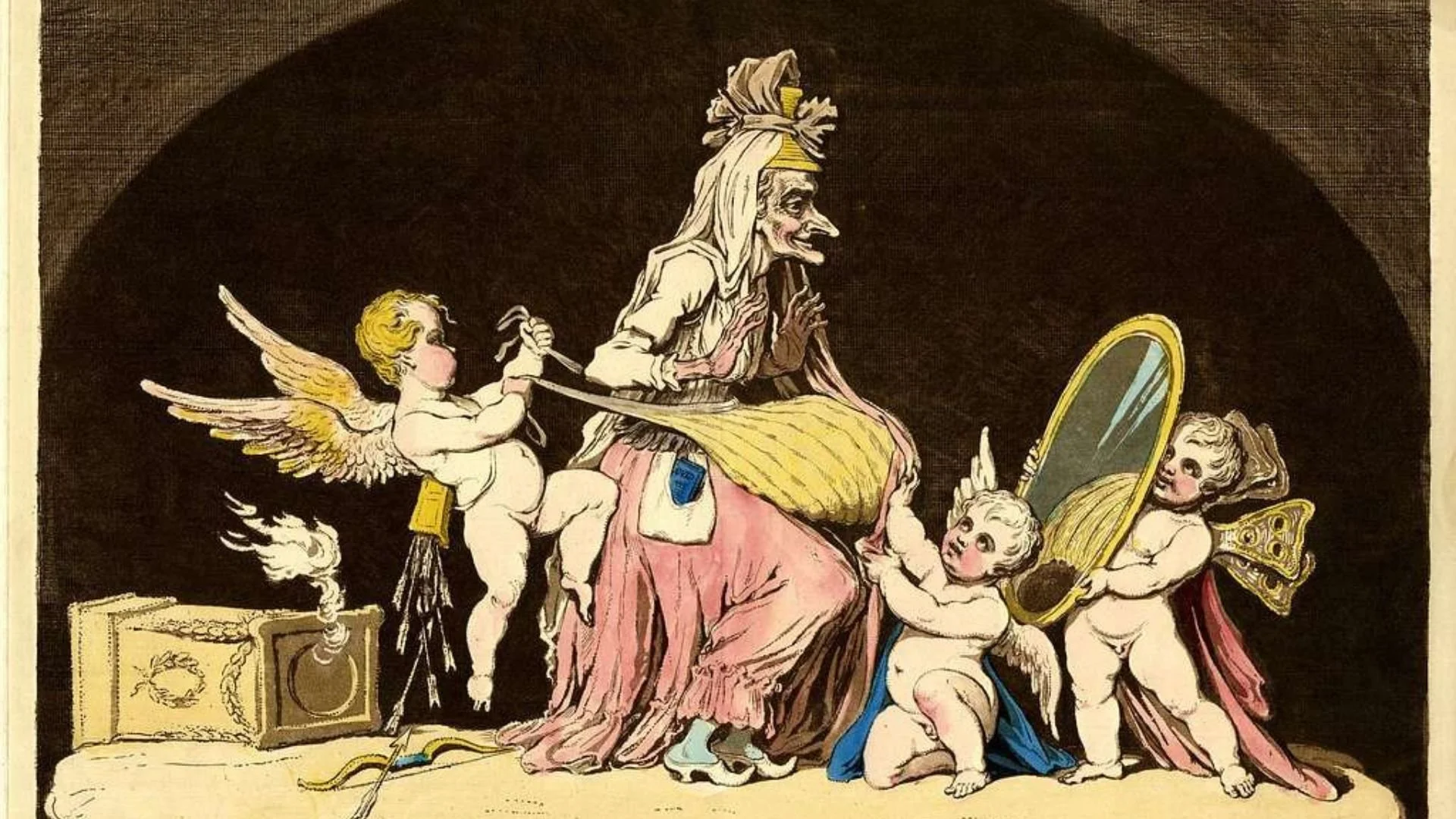

A political cartoon. The sacred hearthfire is overturned on the left, while an old Vestal Virgin tries to look appealing. Public domain, Picryl.

So, circling back to that question—when did ancient Rome fall? For Coelia and those like her, the Rome they knew—even if it was just shadows of what it used to be—probably fell in 394 or 395 CE, shortly after the battle of Frigidus, when the sacred fire of Vesta was extinguished on the order of the Christian emperor Theodosius.

For everybody else, the fall—at least part one of the fall—happened a short 15 years later when the Visigoths, led by Alaric, sacked Rome in 410 CE. And then we might say the final death blow to the Western Roman empire was when the barbarian Odoacer deposed the emperor Romulus Augustus in 476 CE.

An Ancient Prophecy, Fulfilled

The sacred fire of Vesta burned for over a thousand years in the same spot. Within 15 years of it being extinguished, Rome did a hard pivot toward decline, and began, basically, a freefall. The ancient prophecy—that Rome would fall if Vesta’s fire went out—thus came true when Rome broke the pax deorum, its ancient pact with the gods.

You’ve heard it said that the victors write the history books, and there are no truer words spoken. Even today there is a tendency to downplay this transition, to dismiss the severity of the laws enacted against the pagans and the emotional toll those took on people like Coelia Concordia. Personally, I think it is time to stop doing that. Those people who lost their freedom of religion, their freedom of speech, their freedom of thought and choice—they deserve better.

Of course, the Roman Empire as we tend to think of it fell for a multitude of reasons spread out over decades, even centuries. All I can say is that I think Symmachus was right—great is the force of custom. It might be sentimental, but I think that to Coelia Concordia, her Rome fell when the sacred fire, the focus of her life, was extinguished before her eyes.

Detail from Las Vestales. Cejudo. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Coelia Concordia’s Life & Legacy

I hope you have enjoyed this article. If you want to read more about Coelia Concordia, please visit the COELIA CONCORDIA page.

On that page, you’ll also see images of the real-life people who are featured in my novel Coelia Concordia: The Last Vestal Virgin of Rome, the seventh historical fiction novel I have written on Ancient Rome and in particular the Vestal Virgins.

These people, along with Coelia Concordia, lived through one of the most tectonic periods in history. And in my humble opinion, it is long past time that their painful yet inspiring story is told.