Vesta and Ancient Roman Religion, at a Glance

The ancient Roman world was polytheistic—Romans believed in and honored multiple gods. The most important of these gods were the dii consentes—six gods and six goddesses. These twelve deities were the Roman equivalent of the Greek Olympian gods.

The Dii Consentes

In Roman religion, the first of these twelve, the god of gods is Jupiter, god of the sky. His wife is Juno, goddess of marriage and women.

JUPITER, God of the Sky

JUNO, Goddess of Women and Marriage

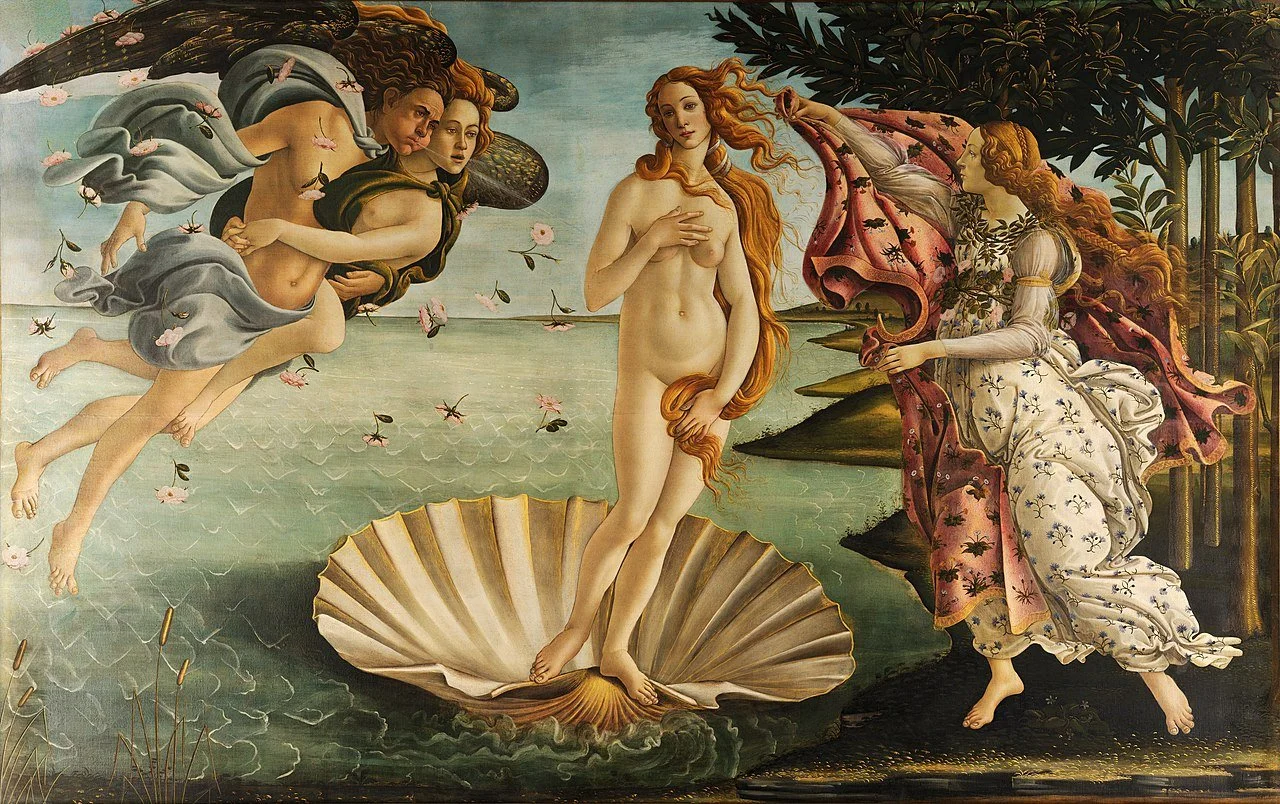

We have Mars, god of war—you might pray to him if you’re a soldier heading off to battle. And Venus, goddess of love—you might pray to her to find true love.

MARS, God of War

VENUS, Goddess of Love

There’s Neptune, god of the sea—you’d pray to him if you’re a sailor. And Minerva—you might turn to her if you need to strategize about something.

NEPTUNE, God of the Sea

MINERVA, Goddess of Wisdom

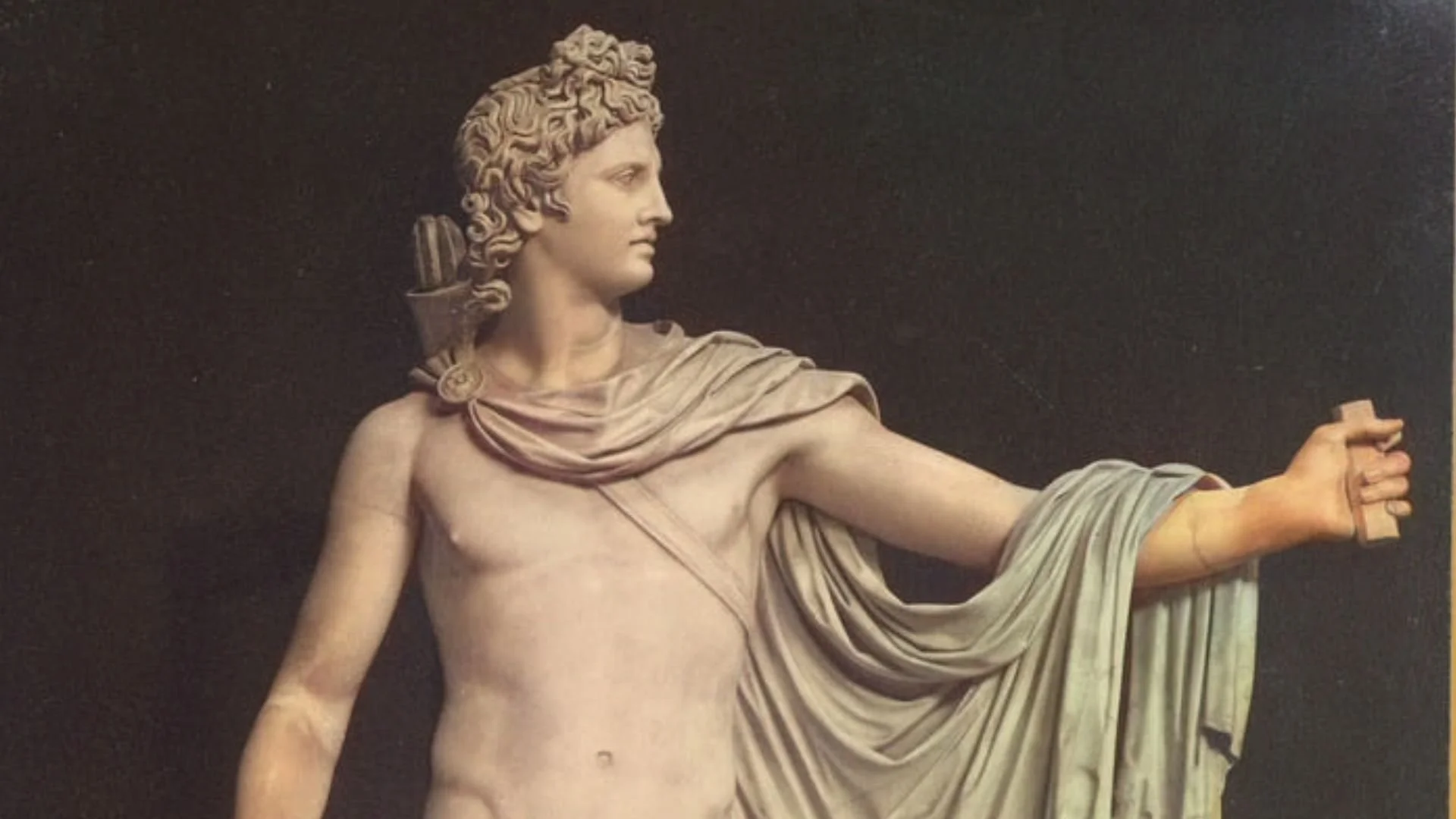

If you’re looking for inspiration or an answer about the future, or if you or a loved one is sick, you might turn to Apollo, the god of light, healing and prophecy. You might pray to his sister, Diana, goddess of the moon and wild animals, before heading out on the hunt.

APOLLO, God of Light, Healing, the Arts and Prophecy

DIANA, Goddess of Wild Animals and the Hunt

And if you’re about to embark on a journey or a new business enterprise, you might pray to Mercury, the god of travel and money. If you’re a farmer, you might offer to Ceres—goddess of the grain and harvest.

MERCURY, God of Travel and Money. Here, he is teaching Cupid to read.

CERES, Goddess of Grain and the Harvest

If you’re a metalworker, you might ask Vulcan, god of fire and the forge, to help you craft the best armor in the entire Roman Empire.

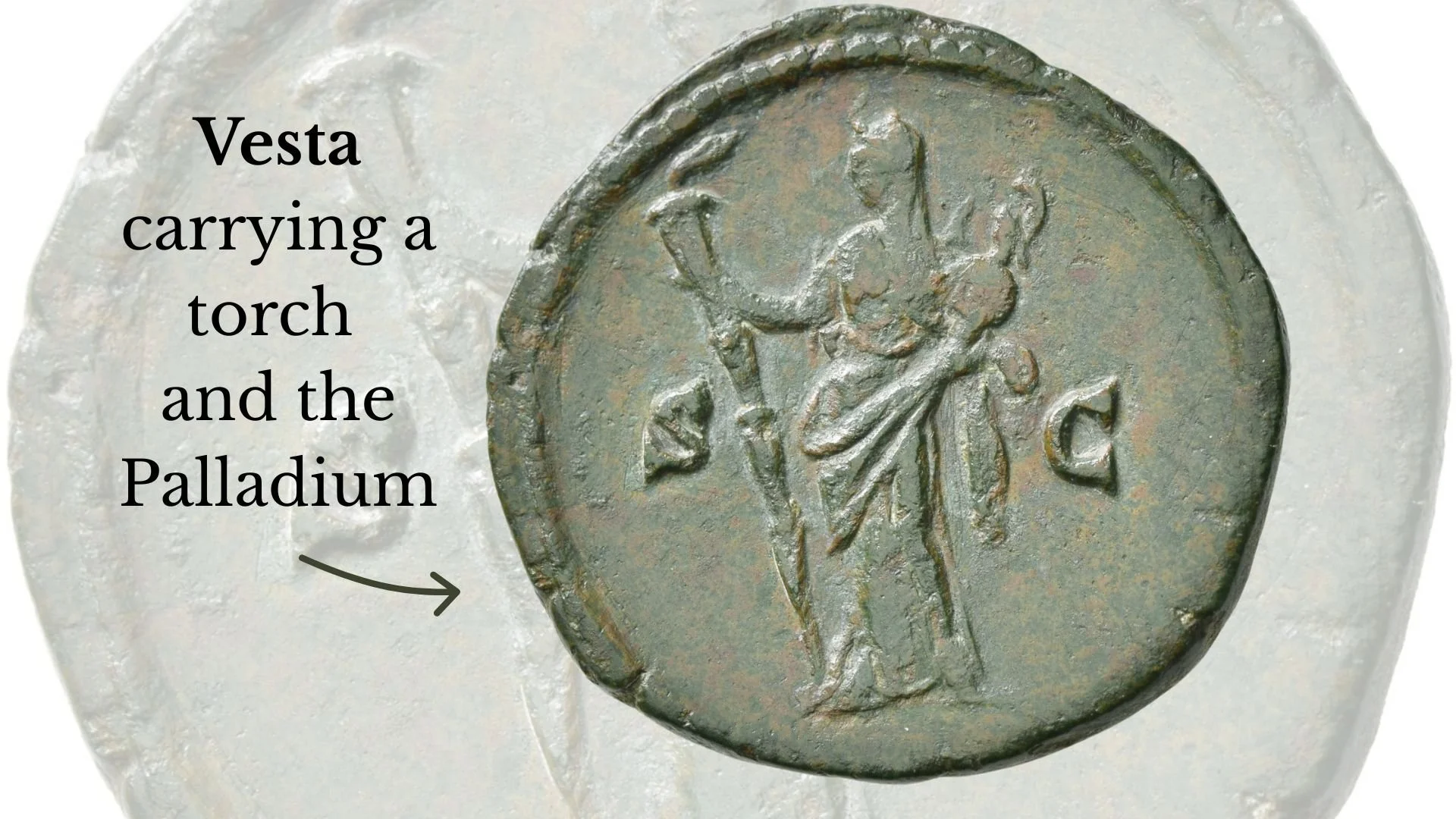

And rounding out the twelve dii consentes is Vesta, goddess of the home and the hearthfire—both the public hearthfire of Rome, which was inside a temple in the Roman Forum, and the private hearthfires that burned in the homes of all Romans. You’d pray to Vesta for the health and safety of your home and those in it, and also to light the darkness with her sacred flame.

VULCAN, God of Fire and the Forge. Here, he is working with the Cyclopes.

VESTA, Goddess of the Home and Hearthfire. Here, she is shown on a coin.

Of course, this is just a very quick introduction to the gods and goddesses of ancient Rome. Because, of course, there was much more to each of the deities I’ve just mentioned, and there were many more deities in Rome.

But suffice it to say, there was something of a balance to the gods and goddesses. They represented the various aspects of the world and the human condition. Life and death, war and peace, joy and suffering. There were gods that roused men to war, and goddesses that comforted women during childbirth. Gods were integral to the family unit and to social order. They were part of everything—the trees, the water, the wine, the fire.

Religion also connected Rome to its past—by worshipping the gods of their ancestors, Rome maintained a certain identity. Tradition, custom, was highly valued.

Inside the Roman Senate House

Living With the Gods… in Peace

Moreover, the ancient Romans believed that Rome’s wellbeing—survival, even—hinged on maintaining the favor of the gods. For that reason, religion was inherently connected to the state. Public and private rituals that honored the gods were deemed necessary to maintain the pax deorum, or the peace of the gods. This was essentially a pact between Rome and the gods, where Romans performed certain rituals in exchange for the gods’ benevolence and protection.

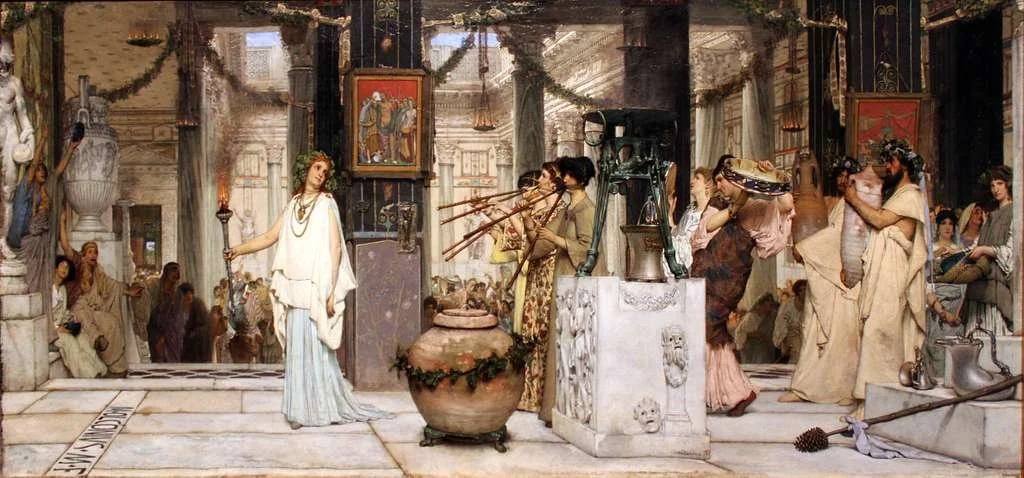

These rituals included animal sacrifice—typically, a hand-raised animal was led to the altar and dispatched by trained victimarii. It all had to go smoothly, since the animal had to go willing to the god. Parts of the animal were then placed on the altar fire as an offering, and the rest consumed by people in a banquet. Yet there were many ways to honor the gods—rituals, ceremonies, festivals, and all kinds of public and private offerings.

Animals being led to the altar for sacrifice

A vibrant Roman religious festival

To honor Vesta at home, people offered bread or wine into their family’s hearthfire at mealtime.

Meanwhile, the Vestal Virgins in the temple offered a variety of things into Rome’s sacred hearthfire—salted flour, incense, pinecones, fruit, olive oil and wine. They performed a variety of prayers and rites.

Their job was to keep the fire going at all times and to keep the goddess happy. That’s because a vital element of maintaining that pax deorum involved maintaining the Eternal Flame of the goddess Vesta. If her fire was neglected, if it went out, Rome would lose Vesta’s favor and the protection of the divine. That is why the order of Vestal Virgins was so important to the Roman state, and why the state so generously funded the Vestal Order.

As with all the gods and goddesses, there were rituals and festivals associated with Vesta. On March 1st of every year, the sacred fire was renewed in the temple. In June, the Vestalia—the festival to Vesta—celebrated the goddess, and gave the women of Rome an opportunity to enter the temple and see the sacred fire with their own eyes.

The Vestal priestesses were also involved in the rites of other gods and goddess, including Mars and Ops—the goddess of plenty—and were responsible for making the sacred wafers that were used in various sacrifices and rituals. You’ve seen these wafers, by the way: the Catholic church turned them into communion wafers.

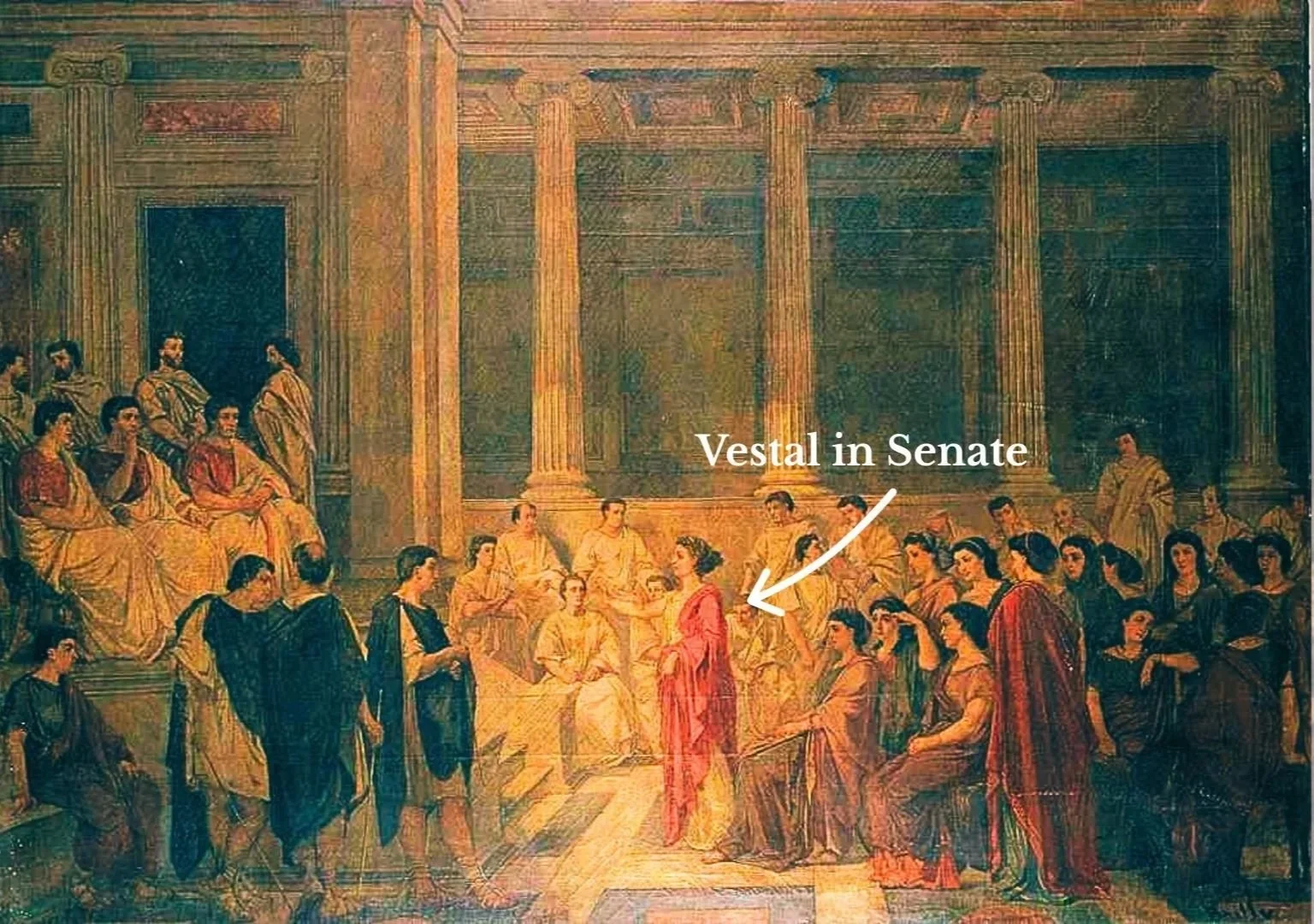

The Vestals were entrusted with other duties too, including safeguarding vital state documents, like the emperor’s last will and testament, and delivering it to the Senate upon his death.

The head of the Vestal Order—the Vestalis Maxima—delivers the will of a deceased emperor to the Senate

So that’s a brief look at the massive subject of ancient Roman religion, and why it was so connected to the state. Yet despite this interconnectedness, it’s important to know that the actual laws of Rome—the legal system itself, as it applied to its citizens—was fundamentally secular. There was civil law and contract law, and these didn’t have much to do with gods. Indeed, many principles of ancient Roman law helped shape the legal systems of Western societies. That’s one reason why you see so many Latin words and phrases in the law.

Because maintaining the law—maintaining order, maintaining the strength and safety of the state—that was Rome’s ultimate concern. And that meant, first and foremost, maintaining the peaceful accord between the people of Rome and the gods of Rome.